Nearly dying something you love

Warning: This article has some pretty graphic images of injuries and broken bones – however it also deals with the subjects of death, grief and permanent disability (as my family were warned this could be one of my outcomes). Please do bypass and head to something a little more upbeat if they’re not subjects you want to confront right now.

When I write this article, it doesn’t bring back terrible memories – they were wiped clean in the accident. But the pain comes from hearing your loved ones recounting when they were told that you’ll either die or spend the rest of your life with life-changing injuries or big personality changes; hit me harder than anything else I’ve dealt with in my entire life.

After more than a decade in the British military, I was used to a lifestyle that embraces personal risks (I use the present tense here as I’m still not sure I can ever completely rule them out of my life). In a single 12-month period, I’d usually spend a month mountaineering; visit 3-4 active or post-conflict zones; spend hundreds of hours developing my Brazilian Jiujitsu skills and then many more running, open-water swimming or looking for new outdoor experiences. Before the injury this year for example; I’d completed the Marathon des Sables desert race, self-funded a fortnight visiting athletes in Kabul, Afghanistan and spent weeks summiting unclimbed peaks in Kyrgyzstan.

However, this year, I also sustained one of the worst injuries I’ve ever experienced whilst trying to climb the Matterhorn mountain in Italy: I slipped and fell a long way down.

When it all goes incredibly wrong

After slipping or being hit by rockfall (we’re not entirely sure what happened up close), I fell 50-to-60m in 5m intervals, hitting my head several times until I came to rest: unconscious and barely breathing.

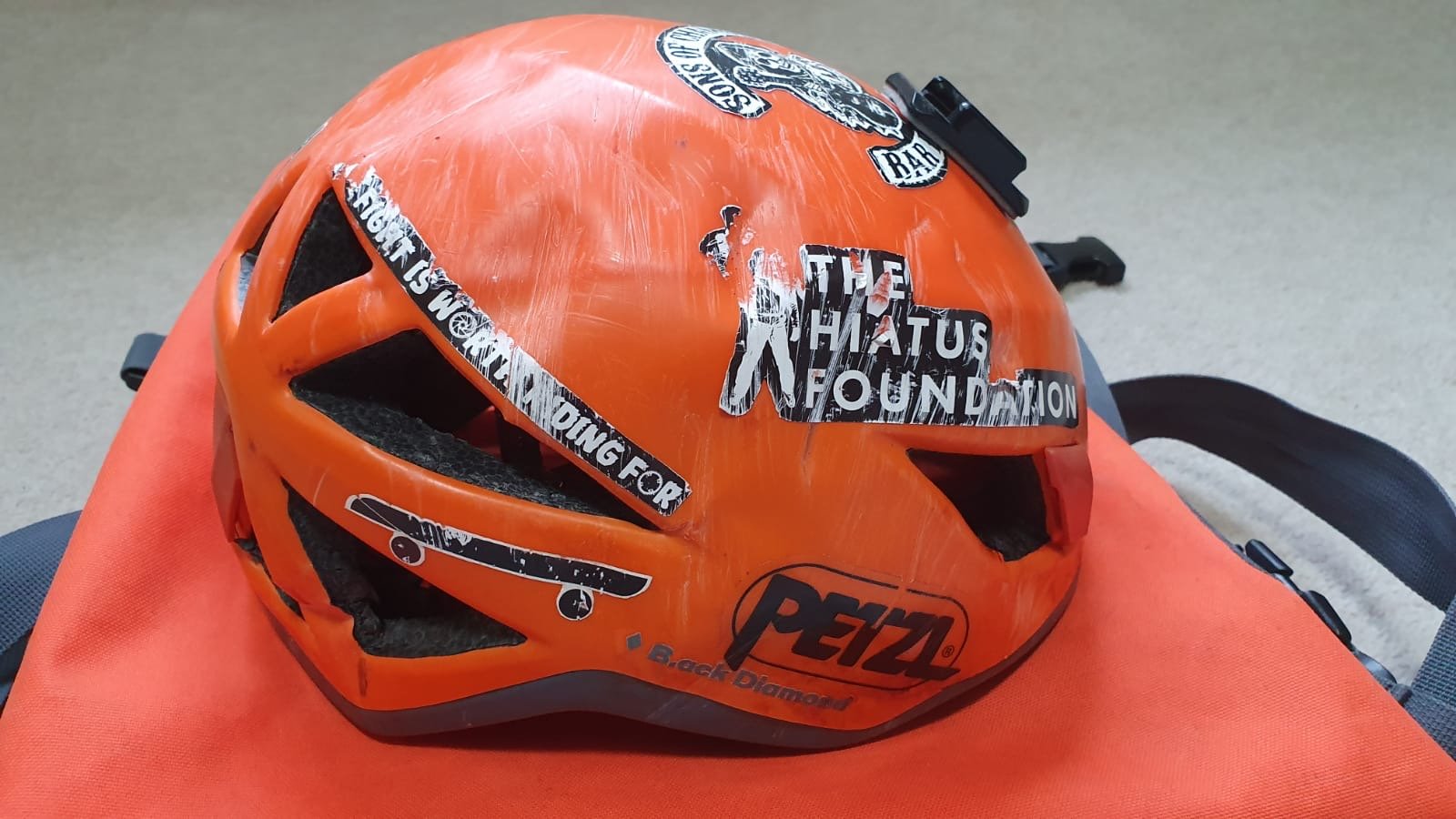

The friends that I was climbing with heard rockfall and saw me mid-fall, thankfully calling the rescue helicopter straight away and giving me first aid when it was clear that I wasn’t okay. When they found me unconscious, I’d already stopped breathing once and had sustained a number of bad injuries all over. Thankfully, my climbing helmet, kept me alive

When I checked it a few weeks after the fall – it was covered in my own blood and looked like it had been hit by a car. Bizarrely, I chose to keep it as a reminder that one day – my number will come up again one day.

Based on what my friends have told me, the helicopter flew me to an Italian hospital in Aosta where a team started to assess and treat me. Their prognosis was bad; the MRI scans revealed a large number of challenging injuries.

Key members of my family and friends flew out to Italy immediately after hearing the news to be by my side. My girlfriend, Anna-Liisa, very diligently made groups and a social media page to inform and update everyone. With Anna, my close friend Duncan and my brother Ben dropped everything to come and see how I was – driving for many hours to get to a London airport from Yorkshire!

The Italian Doctors – specialists in mountain trauma, - nervously told them that I may die from the fall or spend my days suffering the consequences of a life-changing injury. Frustratingly, it was hard to predict how I’d bad the damage would be until I came out of the coma – which was showing no signs of letting up to my family and devastated partner.

Although the worst-looking injury was a badly fractured lower-leg (whereby I’d broke the tibia and fibula), I had severe legions (blood clots) in different parts of my brain which. This was terrible as it would I could be left in a really bad mental place from these – it I woke up at all. The medical staff and my family shared the perspectives that I’d find it hard to make a full recovery from this.

As a relatively new mountaineer (I’ve been climbing for around 5 years however have spent many days in the mountains as former-Royal Marines officer. Unsurprisingly, I didn’t expect to have such a bad fall.

The battered Black Diamond helmet that undoubtedly saved my life

The recovery

I woke up from the coma 8 days after the accident and couldn’t talk and struggled to recognise faces and people. I was surrounded by my girlfriend and two close mates – but my head was full of haze, only exacerbating their worst fears.

By the second and third days, I was talking but making mixed sense by using the wrong words in sentences.

Not long after, I started to ask what had happened and wanted to understand what I’d been through.

Over the coming weeks, I started to regain cognitive, mental and physical skills to take ownership if my recovery.

Thankfully, I’d insured the trip with the British Mountaineering Council (BMC). By engaging with my friends and family, they organised my return to the UK - escorted by an English Doctor and Nurse - and took me to a London hospital to help me to recover. Even if you are taking a relatively easy trip, I’d advise people to ensure you know how (and where) to raise the alarm – you never really know how bad it’s going to be.

Unexpected issues arising from the injury

Head injuries

Despite having many active interests throughout my life, this was one of the worst injuries I’d ever had: My leg was broken in a number of places, but mainly it was the traumatic brain injury (TBI) that caused the problems; the brain is such a challenge to understand that predicting the extent of injuries could be like making a wild guess as your age, fitness, development and the accident are all factors in your recovery.

Trying to understand the extent of cognitive and mental damage is still a challenge (especially if you didn’t know the patient beforehand).

Well wishers

The strange thing about those wanting to make-sure you’re okay, is that they can distract from your rehabilitation in the long time.

Axiomatically, I found that it was great to be surrounded by people in the weeks after I woke from a coma – it made me feel that the injury was only a short-term thing and I’d bounce back to normality as usual happens with injuries.

However, in the later weeks as I was trying to get back into a normal routine of work; visits would interrupt my though patterns – and the conversations would head back into ‘safe’ territory of “how are you? How are you feeling?”. Whilst these are fine in the short term, they do prevent the patient from deeply considering the incident fully until the quiet hours when they’re alone.

Waking up after the coma

Feeling responsible for the accident

It’s hard not to feel responsible for taking a fall on a mountain. When your day job consists of learning to walk on difficult terrain with heavy gear, you feel like you should be up to the task even if you’re not.

However, as you’re there for your own enjoyment of the scenery and experience – and not being tested; you don’t ever feel that you might die doing it.

Combination of injuries affecting your recovery

I didn’t realise that having a head injury and broken leg would be such a challenge to recover from. It essentially stopped me from doing the adventure sports I love climbing; whether that’s running, swimming, climbing or Brazilian Jiujitsu. Essentially anything that could result in head or leg injuries will be off limits.

Summary

Ultimately, the fall on the Matterhorn will put me out of action for many months this winter. It’s affected my career, relationships, lifestyle choices and many other connected areas.

It’s not something one can really learn from or avoid repeating – accidents are just that; unplanned events that we have marginal control over.

And whilst it is easy to feel down about the things I can’t do until I’m fully healed, it’s also an opportunity to realise that I as bad as this experience has been; I don’t want to stay out of the arena – I just have to figure out a way to get back into it.